Named after the 1920s fraudster, Charles Ponzi – who promised investors 40% returns on their investments in 90 days, compared with 5% interest earned in savings accounts – the Ponzi scheme is the oldest and most common type of investment fraud. In its simplest form, a Ponzi scheme is essentially a pyramid scheme that operates on the basis of ‘robbing Peter to pay Paul’. The promoter pays the initial investors enormous returns using the investments of later investors rather than from business profits. Ponzi schemes generally have no viable business model and very rarely generate any legitimate profits of their own. Their survival is dependent on a constant flow of new investor money which, if not found, will result in the ultimate collapse of the entire swindle.

In most Ponzi schemes, the promoter and early investors will make the most money and live lavish lifestyles, whereas the later investors will inevitably lose everything. In the early stages of a Ponzi scheme’s existence, the promoter pays out high returns ‘as promised’ in order to build trust with the early investors and encourage new investors. Once the supply of new investors inevitably dries up and the promoter is unable to pay out returns, investors become suspicious and distrustful. Sadly, investors are often slow to admit that they’ve fallen victim to a Ponzi scheme. Besides the understandable anguish of being perceived as both foolish and greedy, many fear that public exposure will create a crisis of confidence that could create a run on the promoter and make matters worse – which is probably how the BHI Trust scheme managed to keep going for over 15 years.

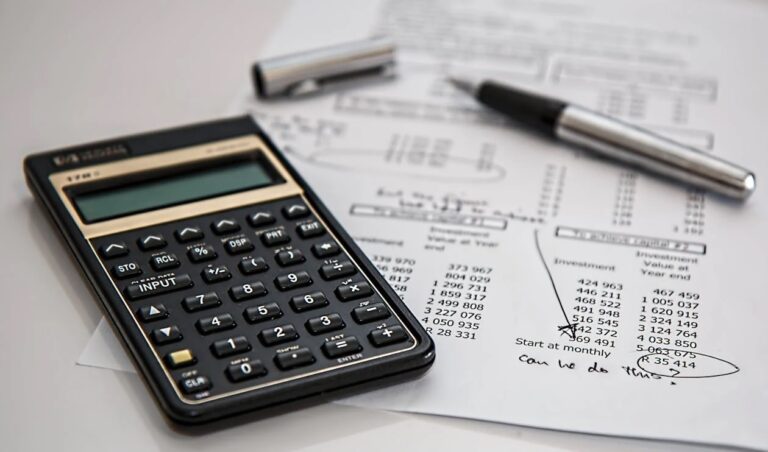

While some claim to be surprised at the unfolding events at BHI Trust reportedly involving more than R3 billion of investors’ money, those affected must have turned a blind eye to the very obvious signs that were on display – with the first being the promise of consistently high returns through downturned markets. While Ponzi schemes can take a variety of forms, they all follow the same intrinsic theme: investors are promised they’ll make a much higher return than can be achieved through any conventional investment opportunity. In the case of BHI Trust, it seems that some investors were promised returns of 20%-plus a year, while one investor shared an investment statement reflecting rolling 12-month returns of 15.18%. Investors were told that the trust founder was a genius trader who had developed a system of buying and selling a handful of local and global shares to make a profit every day. By their very nature, investment markets rise and fall over time, and investment returns in any reputable investment should reflect these market fluctuations. As such, advisors and investors in BHI Trust should have been highly sceptical of the promises to generate consistently positive returns despite adverse market conditions.

From a compliance perspective, none of the forms of BHI Trust seem to have met the basic disclosure requirements of FAIS and no FP numbers could be found for any of the parties. In addition, the investment had no website or marketing material, and the trust founder ostensibly kept a low profile with no social media presence – with his modus operandi being to work his school’s old boy network, which is textbook Ponzi scheme. Ponzi scheme promoters are notorious for creating an air of exclusivity by luring would-be investors into their inner circle of family and friends. By proximity to those who are close to the fraudster, investor fears are allayed because, after all, foxes never prey near their dens and thieves don’t rob from their own homes. This is a powerful psychological tactic used by fraudsters to build credibility through association with reputable people who are known to them. Remember, Bernie Madoff managed to deceive those nearest and dearest to him, including his own two sons.

A number of organisations and individuals raised concerns about BHI about 10 years ago, specifically around the use of a trust to house a collective investment scheme, although seemingly this was done by the trust founder to get around FAIS compliance. Other concerns raised were that the client investment statements were short on detail and substance, that returns quoted in correspondence showed improbable returns year in and year out, and that the fees charged were relatively high compared to industry standards. If entertaining clients abroad, driving around Sandton in his Ferrari and living a lavish lifestyle were not dead giveaways, the rest of the warning signs should have been.

While hoping this is the last time we’ll have to share the warning signs of a Ponzi scheme, it’s unlikely to be the case. That said, investors should heed the following:

- The survival of any Ponzi scheme is dependent on its ability to continually attract new investors. Without an ongoing stream of new investors, the promoter is unable to pay the previous investors, and the whole scheme will unravel. If you are pressured into finding new investors or offered rewards for introducing new investors, alarm bells should be ringing.

- Ponzi schemes will collapse without regular income or if too many investors withdraw their funds. In order to remain afloat, the promoter will offer investors higher returns if they don’t cash out or if they reinvest their money. While on paper investors believe their investments are gaining incomparable ground, the truth is that most Ponzi schemes don’t make any investments on behalf of their investors at all. If you’re pressurised or rewarded for reinvesting, be alarmed.

- Ponzi fraudsters are also notorious for creating a false sense of urgency by leading the investor to believe the deal is only valid for a limited period of time. The investment opportunity is often shrouded in secrecy, and the investor is pressurised to ‘act now’ while the ‘once-in-a-lifetime’ window of opportunity stands obscurely and suspiciously ajar. Pressure to invest within a certain period of time is foreign to sound investing principles and should be considered a red flag.

With this in mind, before investing in any company, here are some steps you can take to verify the investment:

- Visit the Financial Sector Conduct Authority website at fsca.co.za and conduct a search using the name of the company you intend to invest in. Ensure that the company or investment is listed and has an FSP number that appears as follows: FSP XXXXX

- Google search the name of the company to ensure that it has a legitimate website that reflects its FSP number, registered address and company details.

- Request the investment performance history from the company to determine whether the returns reflected are in line with the rest of the market.

- Get a second opinion from an independent financial advisor who holds the Certified Financial Planner® An advisor with integrity and with your best interests at heart will likely not charge for a consultation and should be able to assist you with your research.

Have a great day.

Sue